Text: Diane Smyth

Images: Misha Maslennikov

Born in 1964 in Dobroe, near Moscow, Misha Maslennikov nearly became a priest before “receiving the blessing to photograph”. He’s shot five major series — Chukotka is a land of loneliness (2007), Kolodozero (2007-09), The lost universe (2008), The Volga Viatka earth (2010), and The Don steppe (2010-12) — some of which show explicitly religious communities, but all of which show small settlements of people living close to the land. To Maslennikov they express something similar either way, and he sends me a poem by Joseph Brodsky by way of an explanation. The opening lines read: “In villages God does not live in [icon] corners / as skeptics think. He’s everywhere.”

“On the one hand, I would like to show the spiritual practice of people who have dedicated their lives to God”, Maslennikov adds. “On the other hand, I try to ensure my images remain within the framework of documentary photography and read for any viewer, regardless of their faith or which part of society they belong to.”

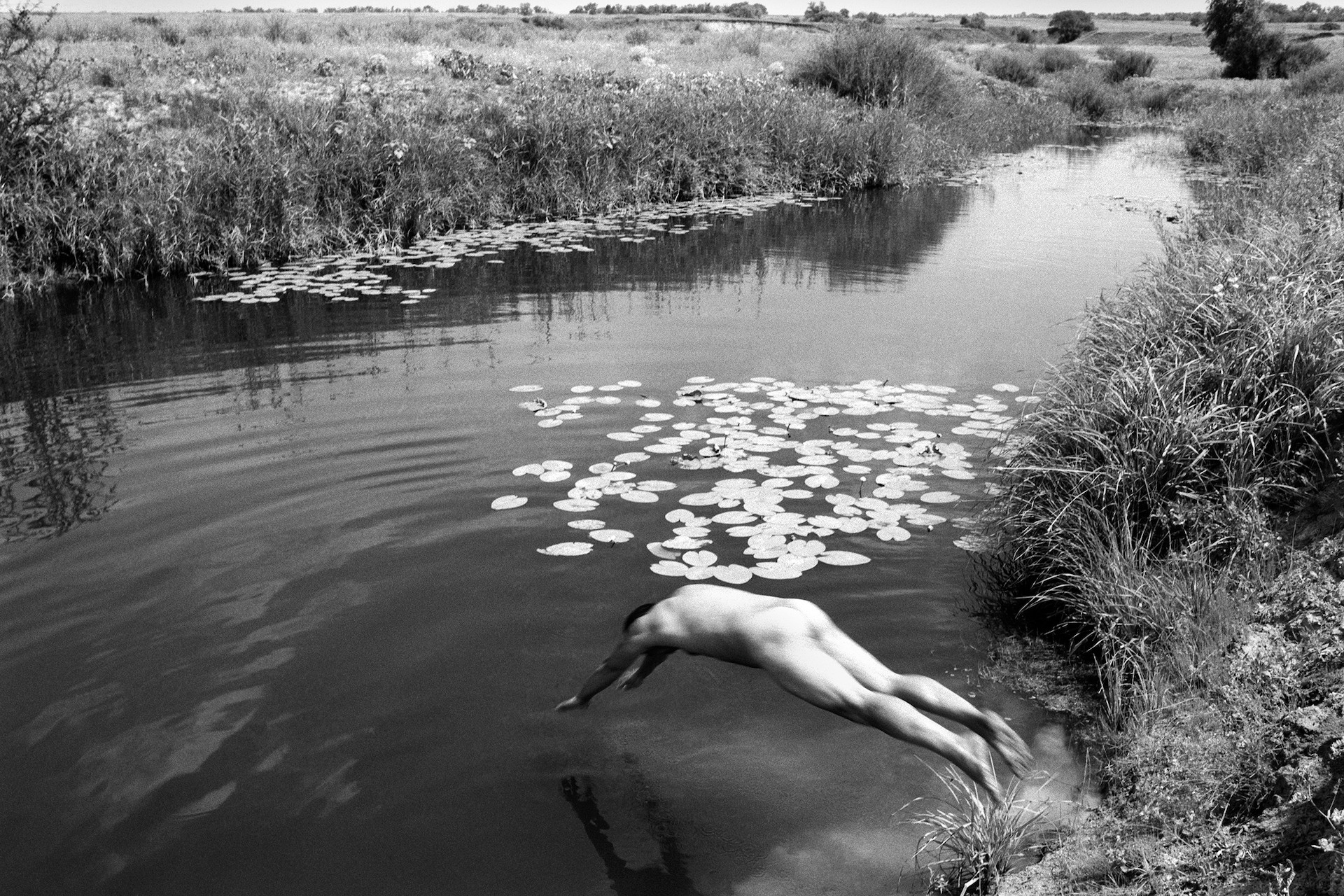

Within this ambition his work ranges from the Far North of Russia, where fishing boats come face-to-face with walruses, to the Don steppe in the Rostov-on-Don region, where people grow melons and swim in the rivers. “In different regions, the nature is beautiful in its own way”, says Maslennikov. “From time immemorial, people have lived in harmony with nature, and in my photographs I pay special attention to their surroundings.”

“In my travels I often encounter many unsightly moments, this is how the world works”, he adds. “But my gaze is mainly directed to the beautiful manifestations of human relationships and the rational coexistence of man with the nature around him.”

The life he shows in Chukotka looks hard; for example, the minority Chukchi people housed in half-empty blocks and old fishing boats rusting away on the beach. But the landscape is beautiful and expansive, the grasslands stretching out under the big sky, bounded only by the mountains and the sea. Within this, Maslennikov hones in on individuals — a priest flying into the region, perhaps, or a 14-year-old learning how to use a harpoon.

He says he loves the Russian North, and his series Kolodozero was also shot there, in the Zaonezhye peninsula by Lake Onega, in the North West of Russia towards Finland. Years ago a group of young Muscovites travelling through the area discovered the abandoned village of Kolodozero, the story goes; falling in love with it they started to go every summer, establishing a summer camp that eventually became a permanent settlement. The community is Orthodox but not overwhelmingly so, he adds, its members as happy to watch a Bergman DVD as listen to a Bible reading.

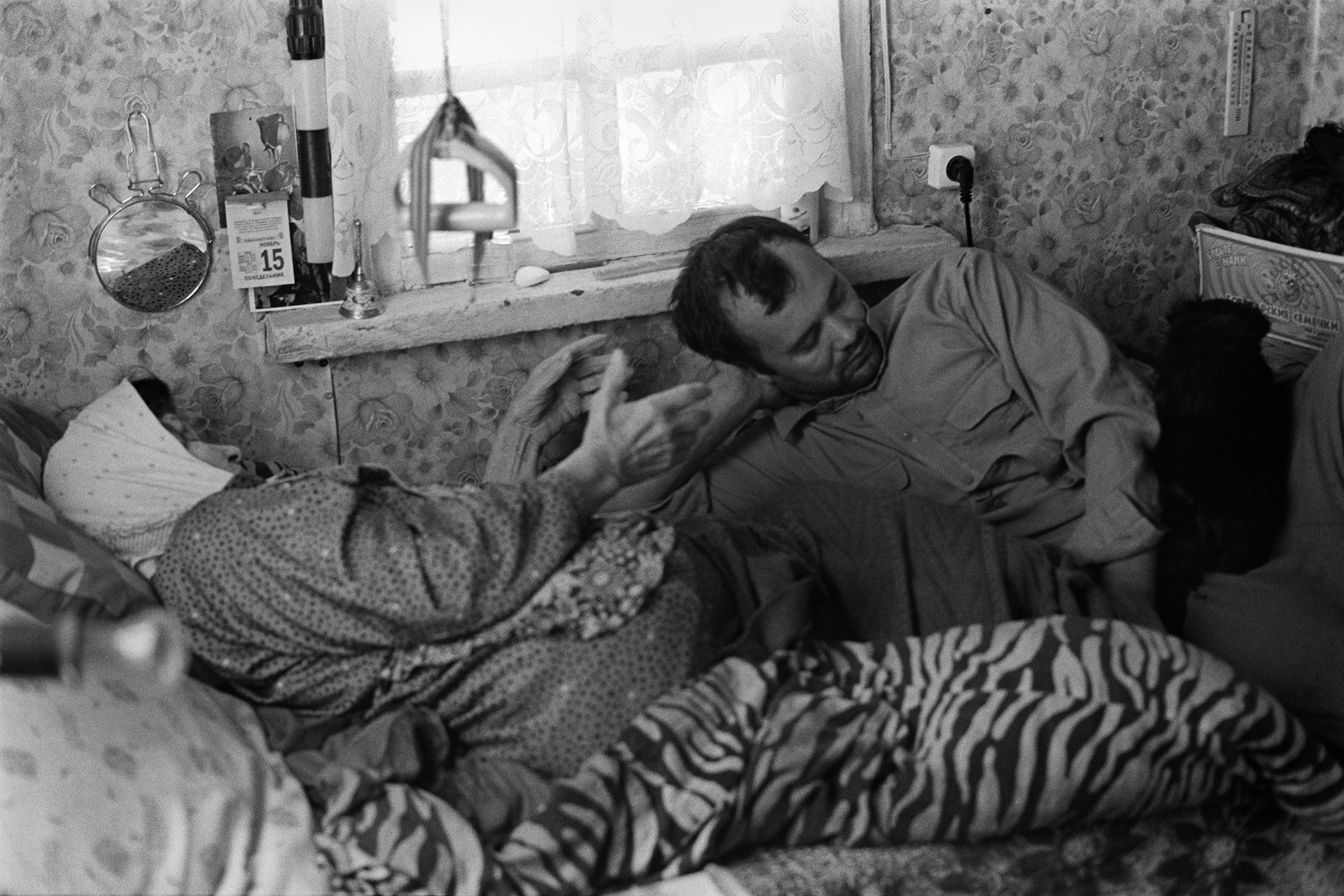

He started going to Kolodozero with friends, visiting several times before he started to take photographs, and seeing first-hand the revival of the village and the reconstruction of its wooden church. One of his images shows a priest baptising a baby in Lake Kolodozero, but other images show more everyday sights such as couples hanging out, or a game of ice hockey. “The living spirit of grace spreads above them and not the dead letter of the law”, states the introduction to the series, written by Yevgeniy Gorny. “Wildness, freedom, and the opportunity to start something from scratch — this is what such places have to offer to people fleeing from cities.”

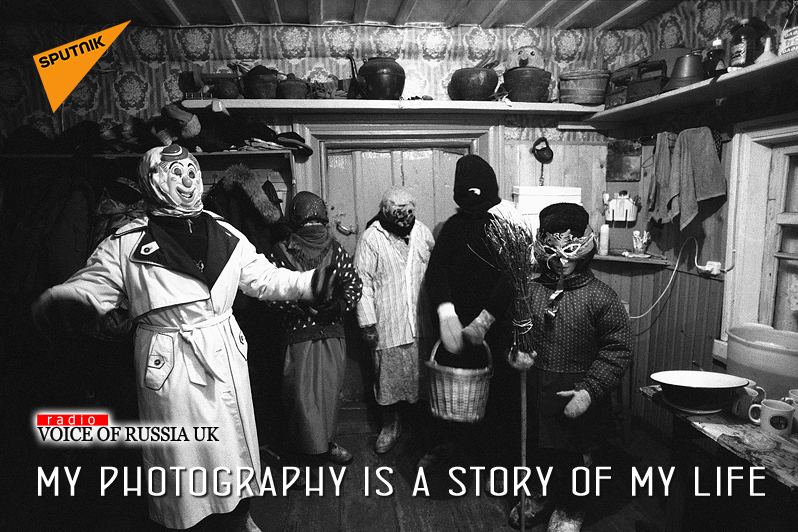

Maslennikov’s The Lost Universe was also shot within a religious community, but this one is in the steppe in southern Russia — in the village of Poteryaevka, Altai Krai district, which borders Kazakhstan. This village was abandoned in the 1970s, as were many other settlements in the area, a process which Maslennikov traces back to the collectivisation of the 1930s and the expulsion of many local families to the Far North. But a religious group discovered the village and started to go there on holiday, setting up an informal summer camp for children which grew to attract like-minded people from across the Soviet Union. Falling foul of both the authorities and the prevailing ideas of the time, the camp faced arson attacks and was nearly closed down for good in 1999, but since the turn of the century’s it’s been permanent, supported by help from the Altai Krai governor and the local Mayor.

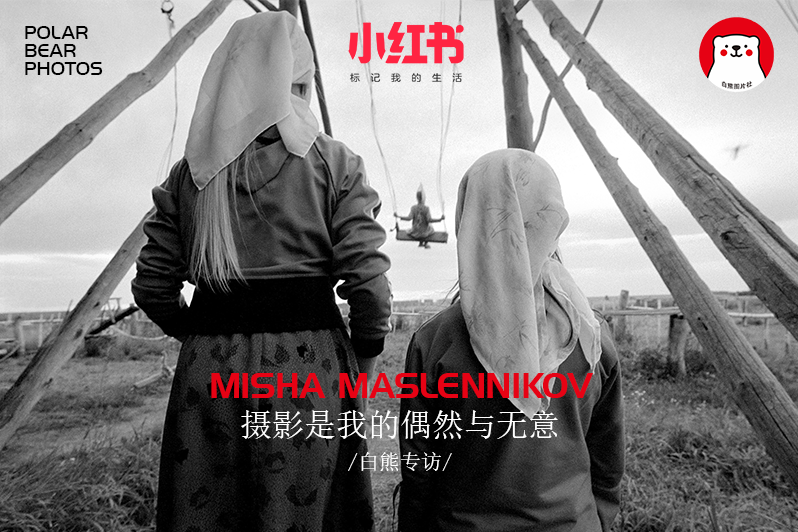

Maslennikov was invited to Poteryaevka in 2008 by a friend, a local photographer called Pasha Bezrukov who regularly visited the Orthodox community. The women and girls all wear headscarves and Maslennikov took photographs of services so it’s clear it’s a religious place, but again, the surrounding nature is an equally important element, from a woman feeding geese, to a man harvesting hay, from a young boy getting a haircut outside, to a shot of an evening bonfire. Maslennikov’s favourite image from the series shows two girls watching another child play on a swing, which he likes because of a just-seen dragonfly.

“That evening, as usual, after a busy day at work, the children rested and had fun before going to bed”, he says. “I took a few shots and was about to leave when, turning around for the last time, I saw a new composition from the back — two girls in the foreground and a third figure flying away into the distance between them. Beautiful, symbolic, figurative. Thought returned, sighted in sharpness, and I pressed the trigger. Immediately, without looking up from the eyepiece, I reset the shutter, when suddenly a dragonfly flew into the frame and hovered in a fat, vibrating spot in the air, practically in the right place.”

“For some reason she seemed important and my mind doubled for a moment — one part concentrating on the movements of the children and the composition of the frame, the other absorbed in the insect…. It flew away at some point, and for two months before the film was developed I was wondering whether it would show up in this single shot. I was lucky, it showed up as an inconspicuous blur, and I was glad of this fortune that smiled at me. The mood of this photograph turned out to be the quintessence of all the images I shot of life in Poteryaevka.”

Maslennikov’s two last series to date move away from religious communities, The Volga-Viatka earth showing life in the rural region his family comes from, and The Don steppe a farming community. The Don steppe is by far Maslennikov’s biggest series so far and he hopes to continue working on it, though for the last few years he’s been pulled into his work leading Noga, the Creative Union of documentary photographers, and also into exhibiting his work internationally. He’s now based in Odesa and first visited the Don steppe with a friend whose mother has a farm there; he says he instantly felt that finding the area was “a gift of fate”.

“The Don steppe is the song of my soul, I can only write about this region allegorically”, he says. “I like the spaciousness and scope of the territory, and the open-minded people, who live almost autonomously in individual farms.”

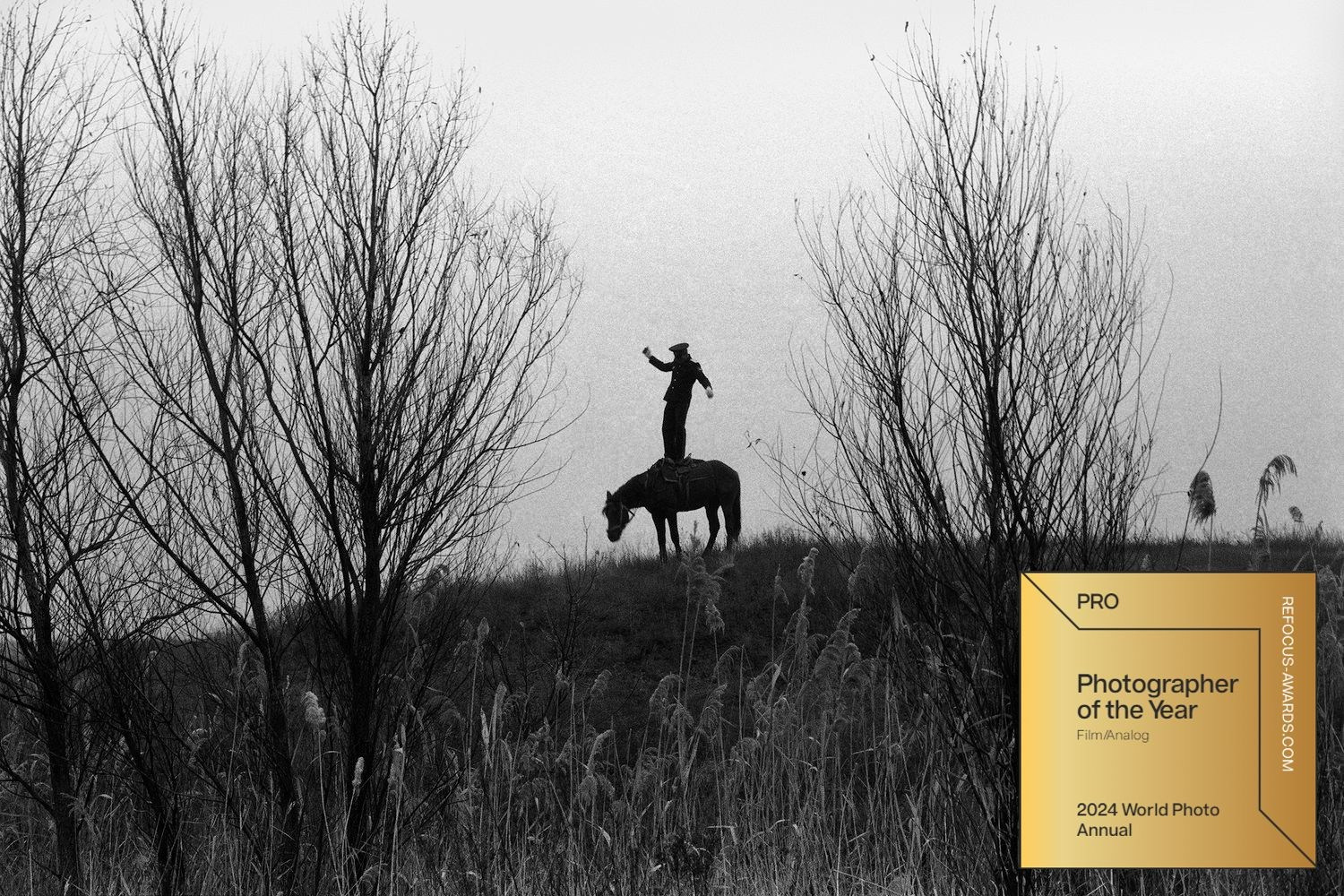

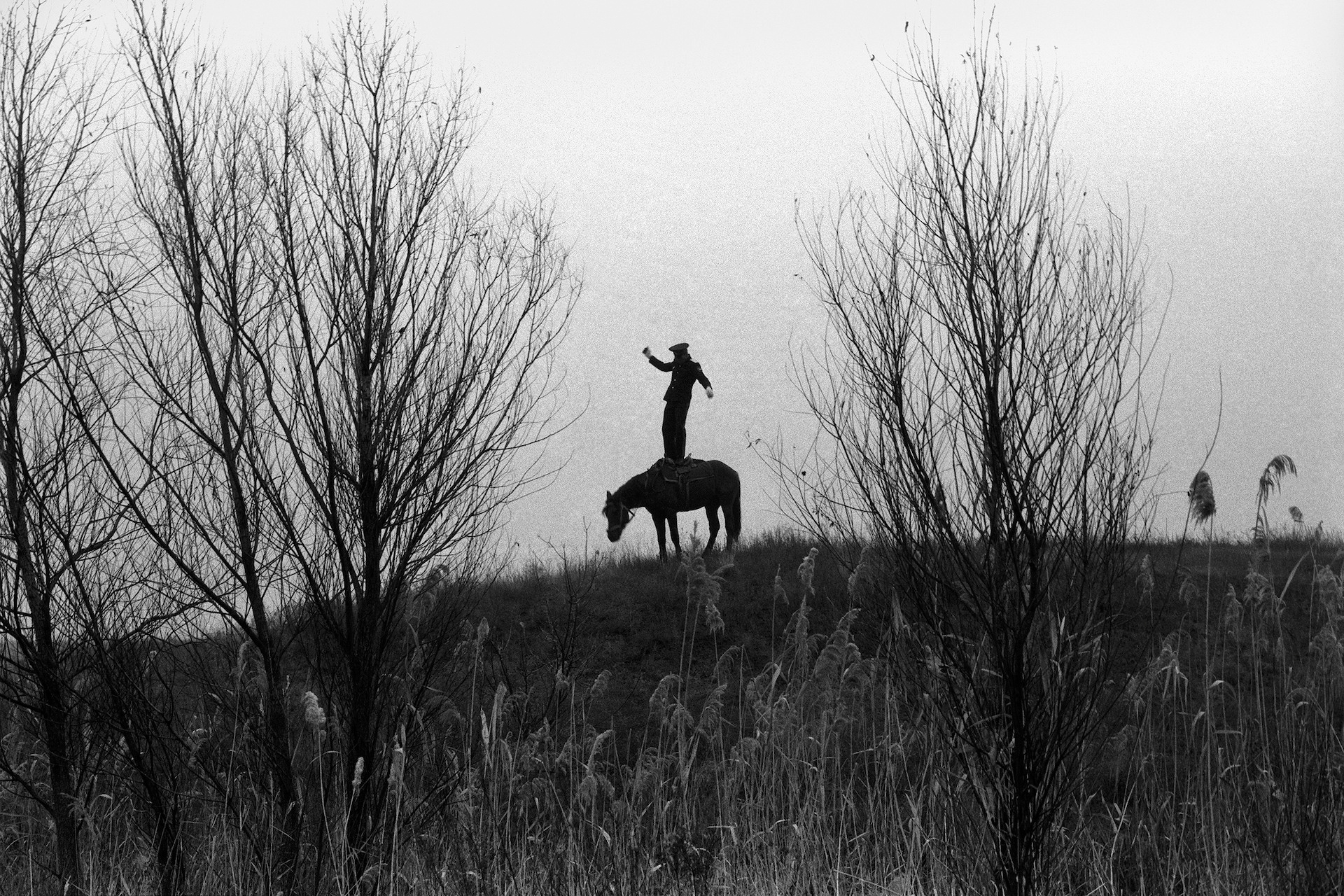

In fact, like all the communities Maslennikov has photographed, these villages are ruggedly independent, in this case partly because of their Cossack heritage. In a stand-alone photostory he’s pulled out of this series, he shows a man called Valerka, dressed in uniform and riding a horse standing up; in the accompanying text he describes how Valerka showed him his great-grandfather’s “ancient service insignia”, proud of his heritage and keen to tell him about it. It’s an independence and military heritage that’s taken on new meanings in the intervening years, but Maslennikov avoids political nationalism in favour of a more peaceful connection with the land.

“Is there another way to live?” he writes. “Well, running the farm there, gardening, the chickens, the cows, the little horse. Gotta feed them. The family too. Everything seems pretty clear. He came to visit early in the morning. Dressed in Cossack uniform, a neat tunic, white gloves. Not for a parade (not in the steppe!), just to look smart.”

новости

Один к Одному 2020

Голос России в Лондоне 2012

Strong Man 2012

ЕКБ.Собака.ru 2012

EXPO 2012

Scriptphotography 2025

Ежегодник всемирной фотографии 2024

Polar Bear Photos 2023

Meet This Photographer 2023

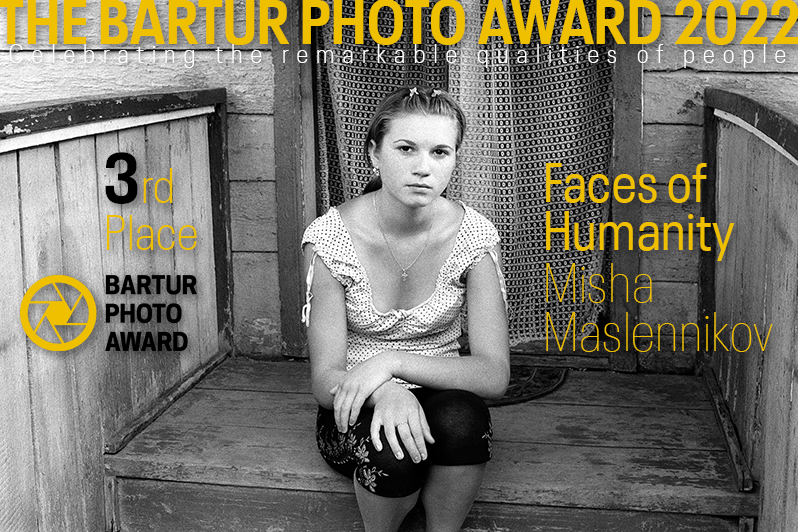

BarTur Photo Award 2022

Immemory 2022

Doppiozero 2022

World Report Award 2022

Альбом ФотоТОП 2021

'In different regions, the nature is beautiful in its own way. From time immemorial, people have lived in harmony with nature.'

Misha Maslennikov who I was lucky enough to interview for The Calvert Journal, looking at his many projects shot in the Russian countryside.