Misha Maslennikov, photographing the steppe

Carola Allemandi

Russia is widely understood today as a complex and tragic theatre, the epicentre of a clash that we still have difficulty in placing and rationalising. This is why noticing a different Russia, portrayed a decade ago, provokes the effect of a temporal and spatial displacement. The work The Don Steppe by Misha Maslennikov, now on show in Lodi for the Festival of Ethical Photography, underlines the term, makes one realise: of a reality, a space, a condition of life. The Russian steppe is synonymous with infinity, for Maslennikov, and in order to define infinity it is necessary to set limits on the horizon that make one realise the spatial scope that lies before us.

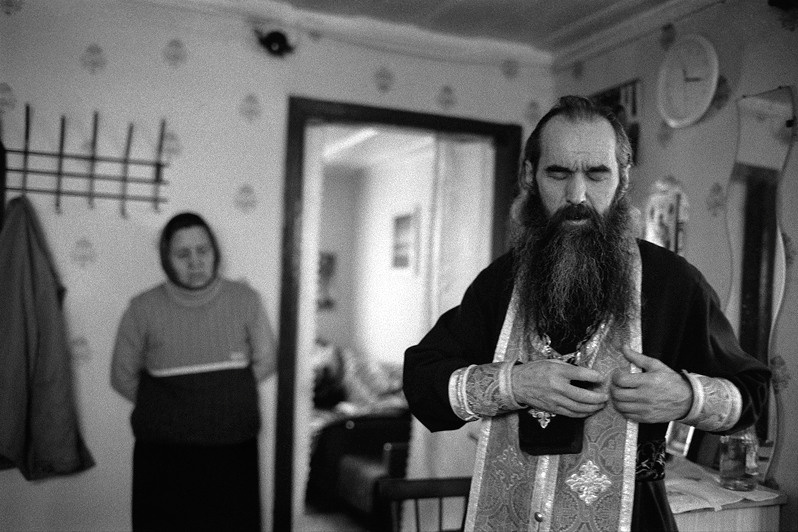

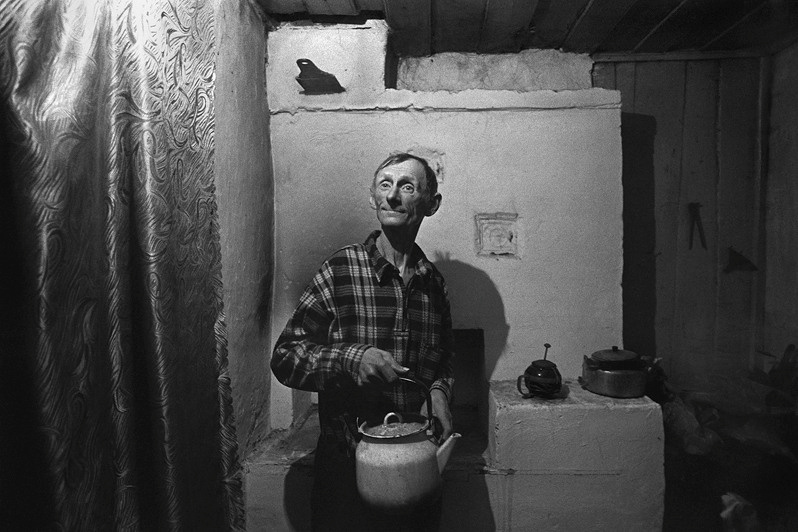

Men — a few — houses, trees and horses are the characters of an age-old tale, the true survivors of history, the bearers of the meaning of what one reads in Chekhov, or in Leskov: in the house of the man marked by the fatigue of work who, as the caption says, is preparing a tea as is customary with guests, one can expect without too much astonishment a liturgical iconostasis, and understand that time can indeed stop and ignore what happens in the one granted to everyone else. The work, displayed here in just 14 images, comprises black-and-white shots taken around 2010 visibly in film, given the happy grain of the prints.

To meet a man from the steppe is to embrace his extension in a few moments — by simple and immediate proportion — as the lady with her arms outstretched with a smile worthy of Lartigue seems to want to tell us; and if it is true that with photography it has become possible to demonstrate the existence of the moment — of the instant that is present and memorable, concrete and sharable — it is then true that infinity can be conceived in the instant and thus imprinted, expressed, communicated.

Entering the steppe, rather than the cold, what prevails seems to be pure white — necessarily camouflaged in grey in the prints — that neutral symbol to which one must get used even when one reaches the Don, totally covered in snow. The white of the steppe — be it snow or sky — becomes in this way a worthy sepulchral instrument, a true arbiter and prophet, capable of burying even that which until yesterday seemed a familiar element. This is perhaps the sense of a work so immune to words — language hardly competes with true vastness — and of images so quiet and taciturn: white becomes aphasic, like those who see it and those who live in it.

Operating by synthesis, photography continuously imposes a sacrifice; in it, easy assertions are annulled, if assertions remain: it implies discarding the whole of reality so that only a fragment of it survives, and that it will look more like the shred of a body that is picked up after being thrown to the lions. This is how the inhabitants of the steppe appear, survivors of the general flow that has swallowed up a large part of a world they seem not to know, living in a state of blissful separation from the rest, doubly survivors in these images.

Maslennikov enters the steppe as those before him did the desert, and in the steppe even children can be totems buried, this time not by snowy white but by water, when the temperature allows it to continue to exist.

The child looks and is silent with a mouth that cannot be seen, covered like the whole earth; the mouth of the earth are its taciturn inhabitants, covered by white and work; and those of those who wake up every day from that white and in the steppe, are daily pasques, like Rimsky-Korsakov’s Great Russian Easter one, but for which no angel will cry 'He is risen!

Entering the limitless place can justifiably make what one encounters appear like glimmers and mirages, like the wagon carrying wood or the stairs leading to the river, or the rare human figures that, like mirrors, remind us how from the outside we too, dispersed there, appear. It is curious to note that in the journey across the steppe to which Maslennikov leads us, in rare cases we enter the shelter of some dwelling: for tea, as we have already seen, to eat, or to attend the confession of an old woman. This scene is understood through the caption alone, as the viewer of the image encounters a priest with his eyes closed, in a bare interior surrounded by a few blurred shadows in the background.

Thus we discover that the interior of the houses is as white as the rest left outside, and the men who pass through that whiteness are only recognisable as black figures, shadows in the shadows, their outlines blurred into immensity. Memory, in photography, does not allow identities to be appropriated, it excludes names, surnames and patronymics from its dictate, and so it is not important to know that this is also lost on those bodies, all the more so because they are devoid of details, even though they are all destined to the same anonymity.

The spirit of these images seems to reside in the total absence of pomp, in the elimination, in having made all the necessary sacrifices: the steppe, like photography, imposes on the gaze a method of synthesis, to the point of being able to conceive emptiness, the light that transforms itself in the white to speak only when it knows that there is no one ready to listen.

The light of the steppe is conscious in an almost liquid calm, uniform on the shadows that also have flesh, bones and life: the clash between the spectres one comes across while walking and the organicity of their bodies is a natural clash with no winners, the duality of men and animals seems to shake the consciousness in favour of a simple acceptance of every condition, which then seems to be the attitude of those who live in these places.

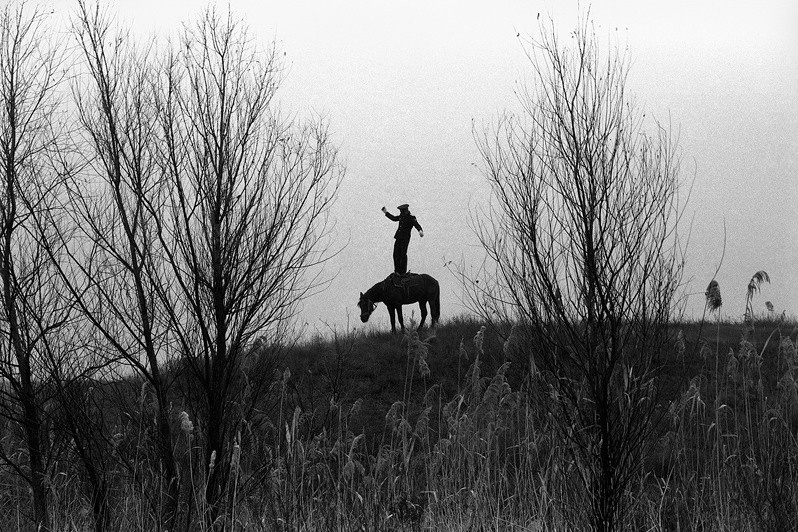

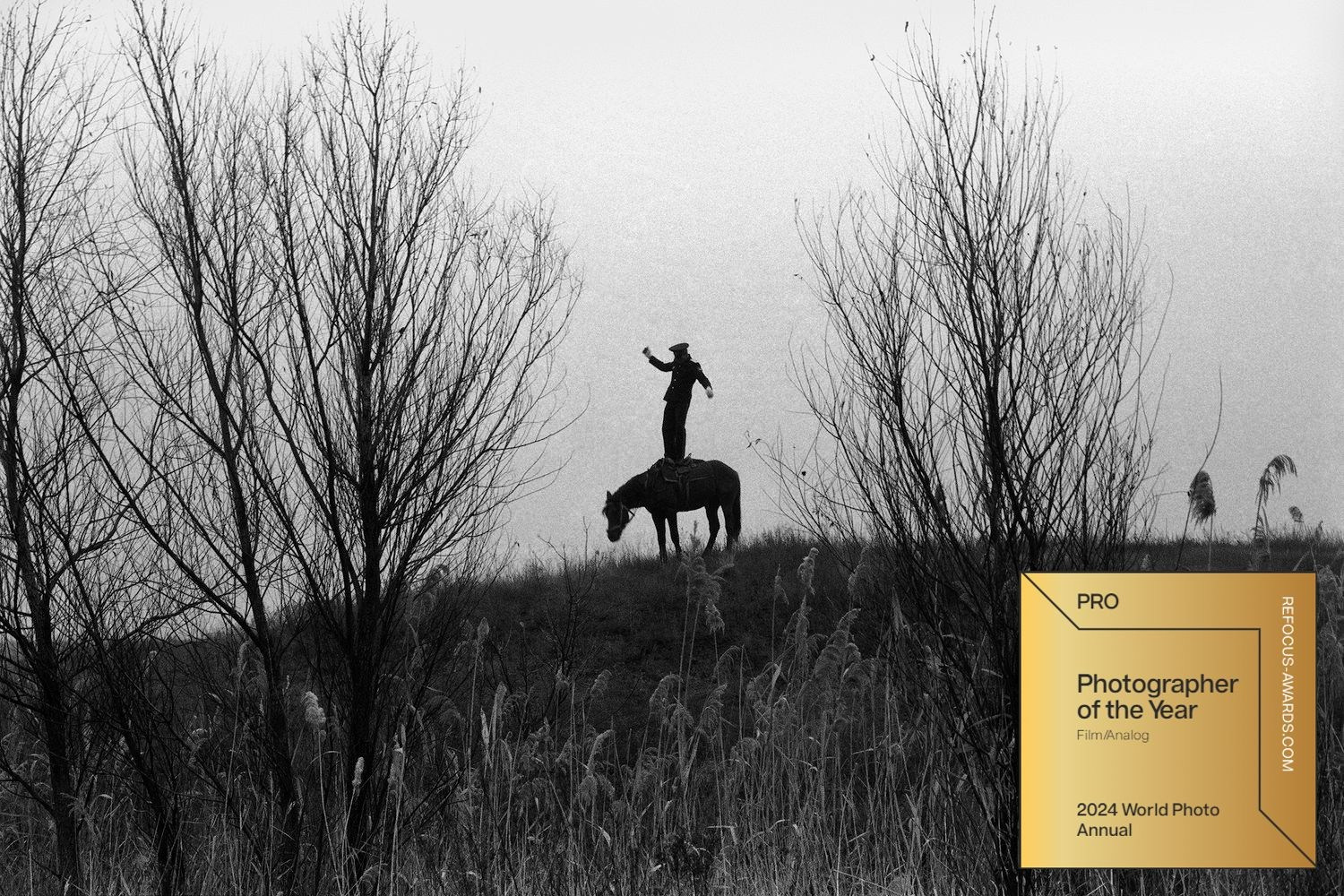

They are shadows walking in the mud, eating the fish caught in the morning, who every moment have the endless ground before their eyes, and who look at it, being able to embrace far greater portions of it than we are allowed with photographic documentation. That is why it seems natural to see a dark figure on the hillside standing on a horse, which if it can be synonymous with spectacle for us, is one of natural freedom for the children of the steppe, who know that even if they were to fall, they would be picked up by the very infinity that generated them.

Since the Festival of Ethical Photography, as its coordinator Alberto Prina states, has as its objective the identification and dissemination of a system of values through the medium of photography, Misha Maslennikov’s work reminds the audience of the hypothesis of an existence solely aimed at life, devoid of ambition; it reminds us that in the infinite what lives does so slowly, participating temporally in what the steppe means spatially. The steppe’s shadow-children are the grain of its own extension, its mortal testimony: it is not important to establish the why or how of this existence, but it is enough to note its resistance to convince oneself of the possibility of an alternative to everything else.

There is a rhythm that does not need to be marked, and that permeates the subterranean sense of living when living coincides with the basilarity of existence. More than of its values, looking at these images, one realises, even before the obviousness of living, the possibility of an unconscious participation in a space and time. This is why, in some of Maslennikov’s images, the horizon disappears completely: in order to cancel out the idea of the horizon, that line that shows us where earth and sky separate, in photography we need to decide whether to look totally towards the sky, or totally towards the earth. Thus in order to be able to comprehend the infinity of the steppe it is sometimes necessary to look only at it, abandoning the idea of a sky that cannot overlook it, as well as no concrete and contemplative horizon.

Such an expanse of land and the life that endures on it offers those who enter it a thoughtful gesture of understanding, of natural welcome, although it immediately warns of the profound rigour that will dominate their every vision, of the gaze that will be destined to oscillate only between predominantly empty spaces.

The steppe, like the man with whom the caption “Only a few metres beyond the fence, the infinite steppe opens up”. For the rest, he will appear as a shadow only capable of looking at us with his eyes, and who will always precede us.

Translation from Italian

Valerio Iglio

news

World Report Award 2022

Album PhotoTOP 2021

PhotoTOP 2021

ZEKE Award 2021

LensCulture 2021

The Calvert Journal 2020

One for One 2020

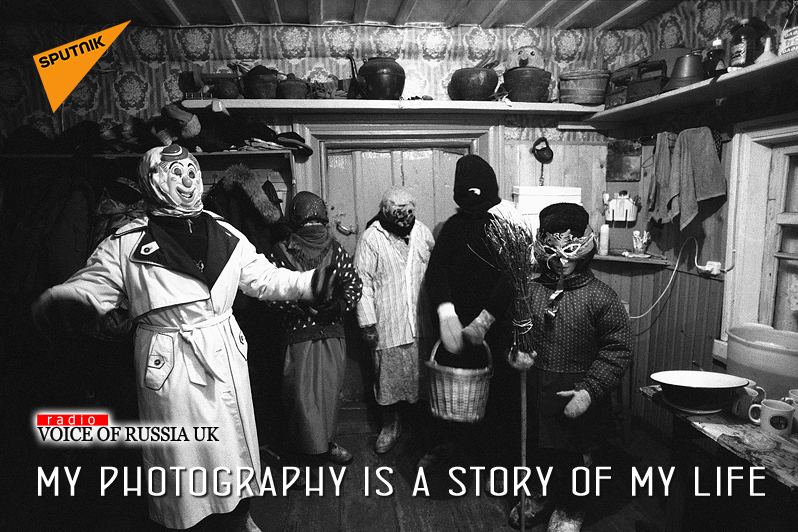

The Voice of Russia UK 2012

Strong Man 2012

EKB.Sobaka.ru 2012

EXPO 2012

Scriptphotography 2025

2024 World Photo Annual

Polar Bear Photos 2023

Ho scoperto la fotografia e lo sguardo di Misha Maslennikov durante il festival di fotografia etica a Lodi, quest’anno. Era stato esposto il lavoro “The Don Steppe”, riassunto in sole 14 immagini. L’occhio di Misha vede ciò che non si può dire, e rende visibili quegli elementi originari da cui l’uomo stesso deriva: lo spazio, l’infinito, il bianco, l’ombra. Grazie a una pulizia formale e una raffinatezza nelle inquadrature che gli sono proprie, pare compiere il suo gesto profetico con leggerezza incomprensibile, quasi angelica. L’infinito spazio che gli uomini che vivono nella steppa hanno negli occhi e portano in giro con sé rivive e si riflette nelle immagini che Misha cattura per fissarle per sempre.

Il bianco e nero e la sintesi estrema sono gli strumenti compositivi che maggiormente risuonano nel suo modo di fotografare, rendendo le immagini delle vere e proprie casse di risonanza capaci di creare un’eco infinita, riuscendo a colmare coi suoi riverberi lo spazio vuoto e sterminato che gli si stende attorno.